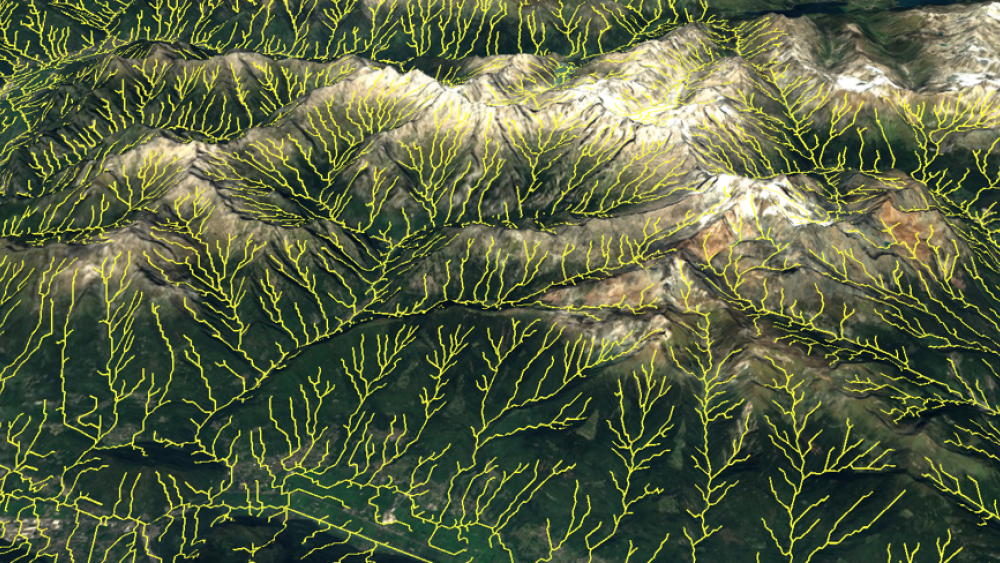

Unlike previous datasets, Hydrography90m also maps smaller and smallest arms of flowing waters. The picture shows a 3D stream network visualization of an alpine valley in the Lake Como area. | Figure: Sami Domisch/IGB

Rivers are the “lifelines” of all land masses on earth. This is also visible in the map that Sami Domisch has developed in collaboration with other researchers from IGB and from Yale University: a finely branched network of potential river sections stretches across all continents. The map is based on the “Hydrography90m” data set, which the researchers spent two-and-a-half years creating on the supercomputer at the renowned US university. Of course, this map is not the first of its kind. Rivers and their distribution around the world are already represented in numerous models. All these maps are based on satellite-derived data of topographic reliefs: wherever there are clefts in the landscape featuring certain characteristics, there will potentially also be a watercourse. And yet no other data set is as detailed as Hydrography90m.

“We took a high-resolution elevation model of the earth and used open source software to extract the river network from it. Unlike other previous data sets, Hydrography90m also maps short and very short arms of flowing waters,” reported Sami Domisch. The level of precision is in the name: the shortest unit is 90 metres long. Since small rivers account for the largest proportion of the global river network (around 70 per cent), they play a particularly important role in riverine biodiversity.

A model calculates the probable discharge from environmental parameters

The data set comprises a total of 726 million potential river sections. The term “potential” is crucial in this context: “Initially, we do not know where rivers are really flowing,” remarked Sami Domisch. The scientist and his team are currently modelling discharges to identify rivers that actually carry water – either throughout the year or intermittently. To do this, they use data from 30,000 gauging stations worldwide where quantities of water have been collected in defined river sections for years. In addition, the researchers have access to comprehensive data on a wide range of environmental parameters such as precipitation, temperature, land use, soil properties, and slope. In the model, these parameters are related to the quantities of water measured in each case. “In this connection, we work with machine learning. This means that with every new data set, our model gets better and better at recognising which parameter variables are related to which water volumes,” explained Giuseppe Amatulli, lead author of the study. If the model works, it can be applied to all river sections worldwide, even if they do not have a gauging station: in this case, the model calculates the probable discharge, i.e. the amount of water in the river, from the environmental parameters available for the entire area.

To validate the model, i.e. to determine whether it works correctly, the researchers initially “feed” it with 70 per cent of the existing water quantity data sets. Trained in this way, the model is then tasked with determining the appropriate quantities of water from the environmental parameters of the remaining 30 per cent. If these quantities are sufficiently in line with the actual measured values, the model functions properly – if not, the model can be improved. However, systematic model deviations can also mean that there are certain parameters – for which the researchers have no data – that play an important role, one being water abstraction by humans. The adapted model can then be used to determine discharges of all river sections worldwide. “In dry regions in particular, it is likely that there are significantly fewer rivers containing water than our data set would suggest,” stated Sami Domisch. This assumption is also supported by a study conducted by authors who used the less detailed HydroRIVERS data set. They estimated that only around 60 per cent of the world’s rivers carry water intermittently or throughout the year.

The model provides answers to key questions: How long are rivers that carry water permanently or temporarily? Where is there a high or low stream density? And what impact does this have on biodiversity? It is also possible to make detailed statements on questions such as these because Hydrography90m captures the catchment areas of river sections on a very small scale. Since environmental data is already available for each of these 5-hectare catchment areas, this data can be used to characterise the existence of species communities, e.g. which climate data or gradients are associated with those communities. For example, various parts of the world have a Mediterranean climate – not only the Mediterranean basin, but also some parts of the west coast of the US. Analysing the species composition there enables researchers to draw conclusions about the biogeography of these habitats, i.e. which environmental impacts contribute to the existence of certain species. And that is just the start of it: “Once we know how much water flows where, we can undertake a detailed analysis of riverine habitats around the world, down to the tiniest river arm,” enthused Sami Domisch. Even in parts of the world that are virtually inaccessible to humans.

The corresponding paper > has been published in Earth System Science Data (ESSD). Data > is available, too.

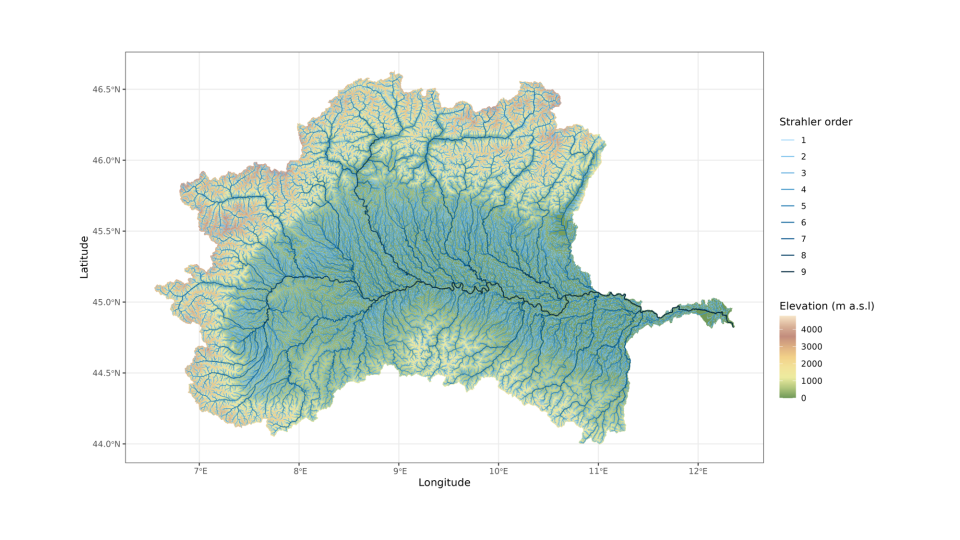

The new Hydrography90m stream segments across the Po River drainage basin in Italy. Darker stream segment colours indicate a higher stream order. The background map indicates the elevation across the drainage basin. | © Sami Domisch/IGB

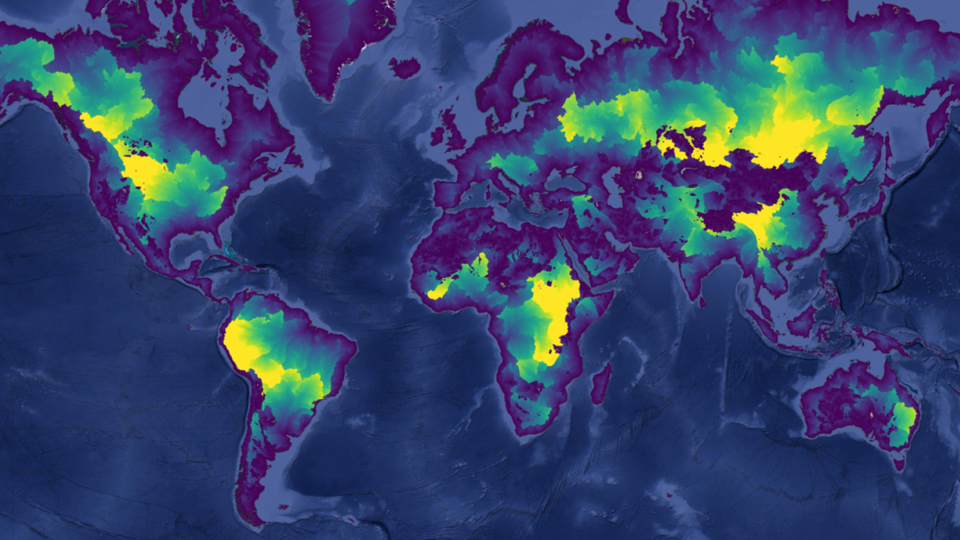

This visualization shows the distance from each river segment to the outlet of the river. Brighter colours indicate a higher distance to the outlet. | © Sami Domisch/IGB

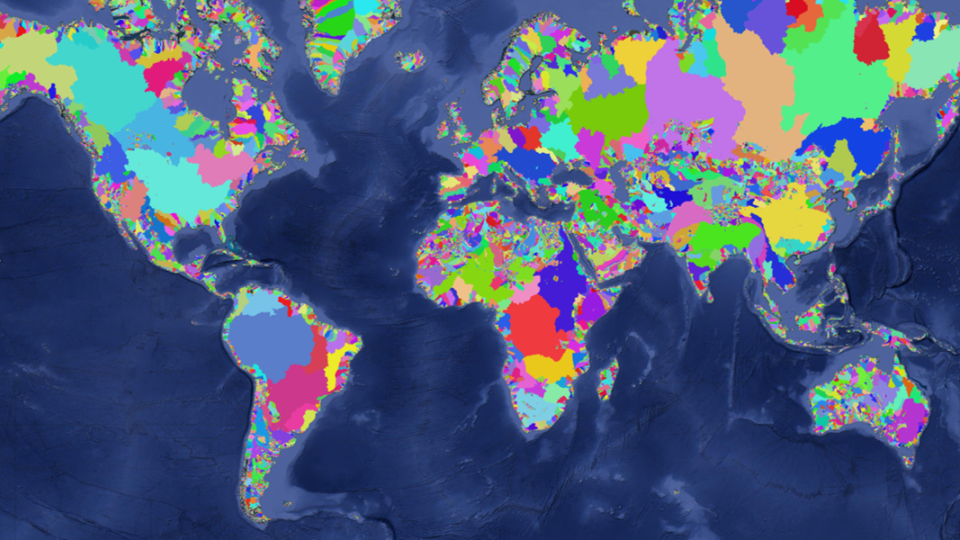

The river drainage basins of the world, illustrated in random colors, delineated at 90m resolution. | © Sami Domisch/IGB