At Lake Gosławskie, one of the five heated Polish lakes, the researchers took samples at different seasons. In the background: the Pątnów power plant, which discharges hot water into the lakes. | Photo: Slawek Cerbin

A number of lakes in Poland have experienced discharge of cooling water from coal-fired power plants for 60 years, causing an average increase in water temperature of 3 to 4 degrees Celsius compared to other lakes in the area. "So, they are just perfect for simulating global warming and giving us a glimpse into future decades," said IGB scientist Justyna Wolinska, who led the study together with her colleague Sławek Cerbin (AMU). To understand how parasitic epidemics spread in warmed waters, she and her colleagues took samples from these lakes and compared them with nearby control lakes into which warmer water was not discharged.

The researchers found that the parasite they were looking for was less prevalent among Daphnia communities in the heated lakes than in the control sites. But what was the reason for this? Did the increased temperature have a detrimental effect on the pathogen? Or were there different levels of host resistance among the Daphnia?

To find out, the researchers also conducted experiments under laboratory conditions. They compared the susceptibility to infection between Daphnia clones that they had previously isolated from the heated and control lakes – in each case at two different temperatures. They were able to show that Daphnia from the artificially heated lakes were less susceptible to infection than those from the control lakes. The experimental temperature had no influence on the incidence of infection.

"In this case, our data do not prove that warming generally leads to more infections," first author Marcin Krysztof Dziuba summed up. "Instead, it depends on the context, how host and parasite dynamics change in a warming world." In the case of the Polish lakes, the increase in temperature may have limited the spread of the parasitic epidemic – for example, by changing lake hydrology, affecting the survival and distribution of pathogen spores. At the same time, the co-evolution of host and parasite in the unheated control lakes may have prevented this pathogen from re-colonising the heated lakes.

"However, we must not forget that parasites are not fundamentally bad," Justyna Wolinska emphasised. If a parasite disappears from an ecosystem, this does not necessarily lead to a healthier state. On the contrary, in the absence of parasites, the functions of the system can be seriously disrupted. That is why it is important to understand how parasites react to temperature increase.

The study was conducted as part of the Paradapt project led by Prof. Justyna Wolinska and Prof. Sławek Cerbin. It is co-financed by the DFG and the Polish National Science Center (Paradapt project) as well as a personal fellowship to Marcin Krzysztof Dziuba, by the DAAD and the Polish National Science Center.

Revisiting the phylogenetic position of Caullerya mesnili (Ichthyosporea), a common Daphnia parasite, based on 22 protein-coding genes

Hunting for Daphnia in Lake Licheńskie, one of the five heated Polish lakes. | Photo: IGB/AMU

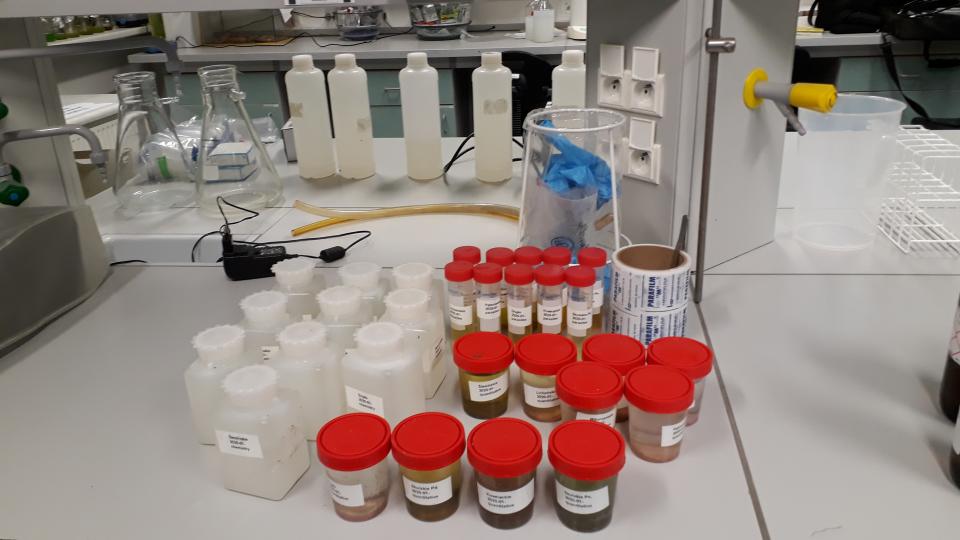

Padadapt samples. | Photo: IGB/AMU

The researchers collected zooplankton samples to isolate Daphnia individuals and establish cultures for experimental assays. | Photo: IGB/AMU

In the evenings, the field samples were processed on site - here by Sławek Cerbin in a hotel restaurant. | Photo: IGB/AMU