What the scientists see in their data is consistent with general observations: Drying soils, creeks that no longer flow, wells that are empty and lower crop yields are easily recognisable signs that water storage is insufficient to support groundwater recharge and evapotranspiration. | Photo: Hauke Dämpling/IGB

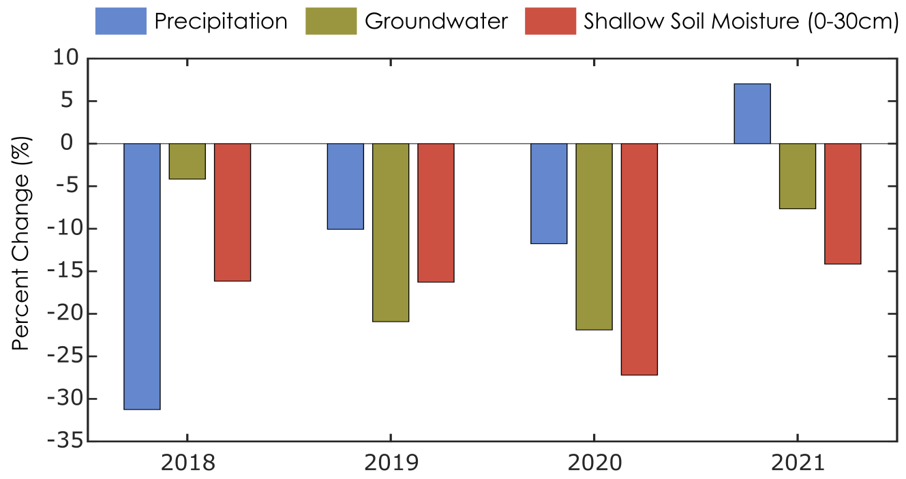

The investigated region in Eastern Brandenburg suffers from drought: In 2018, 30 % less precipitation fell compared to the long-term average. In the two following years 2019 and 2020, it was 10 to 15 % less in each year. And in the current year, too, there was too little rain until June. But how do periods of drought affect our water resources? And how much precipitation is needed to compensate for the shortage?

In order to assess these questions, IGB researchers are investigating how water is distributed across the landscape, how it runs off and how much of it can be stored. Since 2018, the research group led by hydrologist Professor Dörthe Tetzlaff has been analysing soil water samples from a 66 sq km groundwater-dominated lowland catchment of the Demnitzer Millcreek, where there are various forms of land use. The scientists are focusing primarily on the vegetation period – i.e. those months in which plants are actively growing. With the help of stable water isotopes and modelling, they quantify groundwater recharge, surface runoff and the evaporation rates of soils and vegetation, and thus also determine the flow paths and age of the available water. In this way, they find out how much water is stored where and for how long in the landscape.

To date, the recent dry years have had an impact on groundwater levels and shallow soil moisture. The data were collected in the catchment area of the Demnitzer Millcreek, a sub-catchment of the River Spree. They show the divergence from the long-term average. | Figure: Aaron Smith/IGB

As the data show, groundwater recharge occurs with a time lag. For example, the groundwater level reached its lowest level in 2020 after the drought summer 2018. It was more than 20 % – or 40 cm – below the normal groundwater level. Even today, despite the increased precipitation in the past two months, groundwater levels are still too low. The situation is similar for upper soil moisture: recent rains have not resulted in the soils being able to absorb enough water. Compared to the average of the last 13 years, about 15 % is missing.

“We would need at least four years of average rainfall, or about 600mm per year in this region, for groundwater levels to recover to pre-drought levels, and one year of average precipitation to replenish soil water storage,” predicts Dörthe Tetzlaff. With increasing extreme events such as droughts, sustainable land management strategies would therefore be needed that are adapted to water availability and increase resilience towards climate change.