Baltic sturgeon from the reintroduction programme were among the victims of the man-made environmental disaster on the River Oder. In the summer of 2022, countless fish, mussels and snails died along hundreds of kilometres of the river. | © Luc De Meester

There was great consternation and unease among the public – initially, there was talk of mercury, solvents, pesticides and heavy metals. For this reason, IGB researchers immediately set about conducting their own, independent investigations. Their scientific detective work soon led them to the biological – but nevertheless man-made – cause. But let us first go back to the start of the disaster:

A deadly wave hits the River Oder and two of IGB’s sturgeon-rearing facilities

9 August 2022

A wave of dead fish reaches the border river. Before that – in late July – there had already been isolated incidents of fish mortality on Polish territory. In response, the municipality of Frankfurt/Oder warns its population not to come into contact with the Oder water or to eat fish from the river. Then everything happens very quickly: within just two weeks, hundreds of tonnes of dead fish are found floating on the river. More than 200 tonnes are recovered, and even greater quantities sink to the bottom or are washed up on the river banks. The creatures exhibit symptoms of suffocation.

10 August 2022 Baltic sturgeon that had been released into the river over the last three years – including more than 1,000 juvenile sturgeon from spring 2022 – also perished in the disaster. “It is impossible to make a reliable estimate of exactly how many of the sturgeon that had been released into the river have died,” states IGB researcher Jörn Gessner. Some specimens, up to 90 cm long, are recovered dead from the Lower Oder Valley. Two fish-rearing facilities operated using water from the River Oder, which contained about 20,000 juvenile sturgeon, are also affected by the toxic wave. Virtually no sturgeon survives the incident. “The fish that perished were just one month old, and were supposed to be released into the River Oder in autumn 2022 to help establish a self-sustaining stock of sturgeon there in the future,” the biologist explains. The events represent the biggest setback for the reintroduction programme, which Gessner has been coordinating since 1996.

Suspicion confirmed: researchers identify the brackish water alga Prymnesium parvum

15 August 2022

Data measured at the monitoring station in Frankfurt/Oder by the Brandenburg State Office for the Environment (LfU) reveal an unusual picture: “Oxygen levels were well above 100% saturation, and pH was elevated. At the same time, we noticed strong fluctuations over the course of the day,” explains Jan Köhler, algae specialist at IGB. “Such dynamics can only be explained by photosynthesis. To us, this meant that we were dealing with a massive algal bloom.” At first, the reason for the high electrical conductivity is unknown. The level increases from 800 to more than 2,000 micro-siemens per centimetre (µS/cm) – such high concentrations in a river can only occur as a result of industrial salt discharges.

Researchers of IGB immediately start evaluating samples, measuring the algal pigment content and fitness, taking photos and preserving samples for genetic analysis. What they find is more than unusual for European freshwaters: large numbers of Prymnesium parvum, a brackwater alga. This species of algae is known to produce a strong toxin that attacks mucous membranes and thin blood vessels, and, in particular, to suffocate fish and molluscs. This alga has the potential to proliferate when there is abundant light, and when the river exhibits low flow velocities, warm water temperatures, and comparatively high salt and nutrient loads. The salt soon proves to be sodium chloride – common “table salt”. It is quickly apparent that the discharges originate from Poland – but the specific company – or companies – responsible for the pollution cannot be identified.

19 August 2022

IGB detects and microscopically identifies Prymnesium parvum in all samples collected from the middle reaches of the Oder. The samples are sent to a colleague at the University of Vienna’s Department of Food Chemistry and Toxicology for toxin detection. “We were able to unequivocally detect significant quantities of a subtype of the algal toxin, known as ‘prymnesins’, in samples taken from various parts of the Oder,” states Elisabeth Varga, a scientist from the University of Vienna. Tests on fish eggs with Oder water conducted by IGB confirm the lethal effect of the toxin.

In light of the findings obtained thus far, the researchers are convinced that it is not a natural phenomenon. “To my knowledge, such a mass development has never been observed before in our freshwaters,” remarks Jan Köhler. “This disaster would not have happened if there had not been man-made discharges and interventions in the river.”

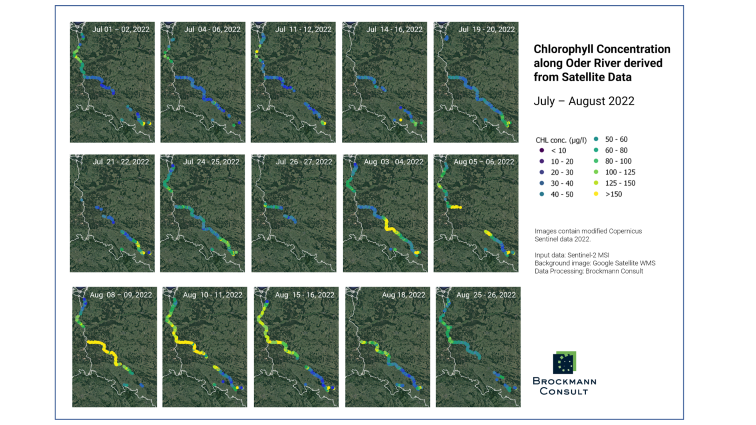

A further indication: satellite data confirm a massive algae bloom

At the same time, IGB scientist Tobias Goldhammer, and colleagues from Leipzig University and Brockmann Consult, a Hamburg-based environmental data analysis and software company, start analysing data from the Copernicus satellite Sentinel-2. They are looking for early signs of the algal bloom and are keen to reconstruct the temporal-spatial development. From the processed raw satellite data, chlorophyll concentrations can be calculated that indicate the algal bloom.

31 August 2022

The dataset is now complete. It shows that in the second half of July, the concentrations in the entire river course were at a moderate level, while in the upper course around the town of Opole (Poland), they were already elevated. At the beginning of August, the chlorophyll concentration spikes near Wrocław (Poland). The algal bloom then spreads very rapidly, covering almost the entire River Oder within a week. It is not until late August that chlorophyll concentrations return to the average level of early July.

According to the researchers’ analysis, the environmental disaster occurred as a result of several stress factors, all of which were caused by human activity. These include development measures that had already reduced the river’s natural resilience to hydrological and climate change: “We see the River Oder disaster as a multicausal, man-made event. There have been frequent occurrences of increased salinity due to industrial pollution in the upper reaches of the Oder in the past, without resulting in such massive algal blooms. But the general conditions seem to have changed,” explains Tobias Goldhammer.

Researchers recommend appropriate measures to protect the ecosystem

12 September 2022

In the wake of the River Oder disaster, IGB researchers recommend protecting and restoring the river and its remaining near-natural habitats, instead of implementing further regulation of the river by means of additional river engineering measures. In 2020, the institute had already warned of the ecological risks of developing the Oder in a previous IGB Policy Brief.

In another Policy Brief, the researchers now recommend a review of the infrastructure project on both sides of the river and the implementation of further measures to stabilise the Oder’s ecosystem and ensure its sustainable use in the future. “The future of the River Oder and its wildlife will depend on whether policymakers and authorities decide to enhance the natural resilience of the ecosystem,” emphasises Jörn Gessner.

First test fishing documents a huge decline in fish stocks

27 September to 19 October 2022

To get a better overview of the remaining fish populations, IGB performs several test fishing procedures in the River Oder. Their results are sobering: species such as burbot, loach, common bream and white bream have suffered massive losses. Larger fish with a body length of 10 centimetres or more are now virtually non-existent.

The researchers are particularly concerned about the Baltic golden loach, which in Germany occurs exclusively in the River Oder. The only known stable population near Reitwein was estimated to comprise about 500 individuals. Not a single specimen can be detected there now. Instead, the IGB team finds ten specimens at Ratzdorf and a single specimen in the lower River Neiße. “It is not known whether the fish fled and migrated from upstream stocks before the toxic wave struck, or whether it is a stable population that has already been existing for a while; nor how long the specimens have been present there,” remarks fish ecologist Christian Wolter.

Also in October, the LfU measuring station at Frankfurt/Oder again shows highly elevated conductivity, even though more water is flowing in the Oder than in the summer months. This means that even higher quantities of salt are being discharged into the river than at the time of the acute disaster situation.

No sign of recovery

29 November 2022

Following the first scientific test fishing procedures along the banks in September and October, the first extensive fishing event in the middle of the Oder since the disaster now gets underway. This inventory is sobering: the scientists catch much fewer fish, and species such as blue bream and asp are lacking completely. In total, the researchers catch only half as many fish as in previous years on average. But not only are there fewer fish: mussels and snails have also almost disappeared. “Data from August already provided us with indications that the Oder disaster has reduced mussel biomass by half,” remarks Christian Wolter. They are the most important filter-feeders in the ecosystem. “It will take a very long time for stocks to replenish, because mussels are not mobile enough to leave their refuge and repopulate areas quickly. This is particularly the case for native large mussels, which also face competition from invasive mussel species,” says the ecologist.

Measurements of conductivity taken during fishing show once again that salinity levels are still far too high for the river ecosystem. At the Frankfurt/Oder gauge, conductivity has been more than 1,900 µS/cm since mid-November already; by the end of November, the figure even exceeds 2,000 µS/cm. The major component of the salt load continues to be sodium chloride. “We detected around 400 milligrammes of sodium chloride per litre of water in water samples from the Lower Oder, which equates to about half of the total amount of salt in these samples. Obviously, large quantities of salt are still being discharged into the river,” explains biogeochemist Tobias Goldhammer.

Looking to the future: a disaster that is bound to happen?

After the disaster, IGB researchers detected so-called dormant stages of Prymnesium parvum in sediment of the Oder. These “dormant” algae can hatch as soon as environmental conditions become favourable again. This also means that there could be a repeat of the disaster when temperatures increase and all other conditions are in place – summer after summer.

Consequently, the recommendations made by IGB researchers remain unchanged. Above all, the river engineering works to deepen the Oder should be stopped: “When we look at the indirect causes of the Oder disaster, low water levels and longer water retention times encouraged the mass development of the alga. Further regulating the Oder would encourage the onset and duration of low water levels, because when water is there, it flows more quickly into the sea in spring. Instead, we need greater retention in adjacent floodplains,” explains Christian Wolter. “To protect the Oder ecosystem, habitats should be restored and substance inputs significantly reduced,” he adds. This also includes switching discharge permits from loads to concentrations for which an ecologically sound threshold urgently needs to be set or complied with.

It may take several years for stocks to recover. The prerequisite would be that measures are taken to improve the situation – and there is no repeat of the disaster.