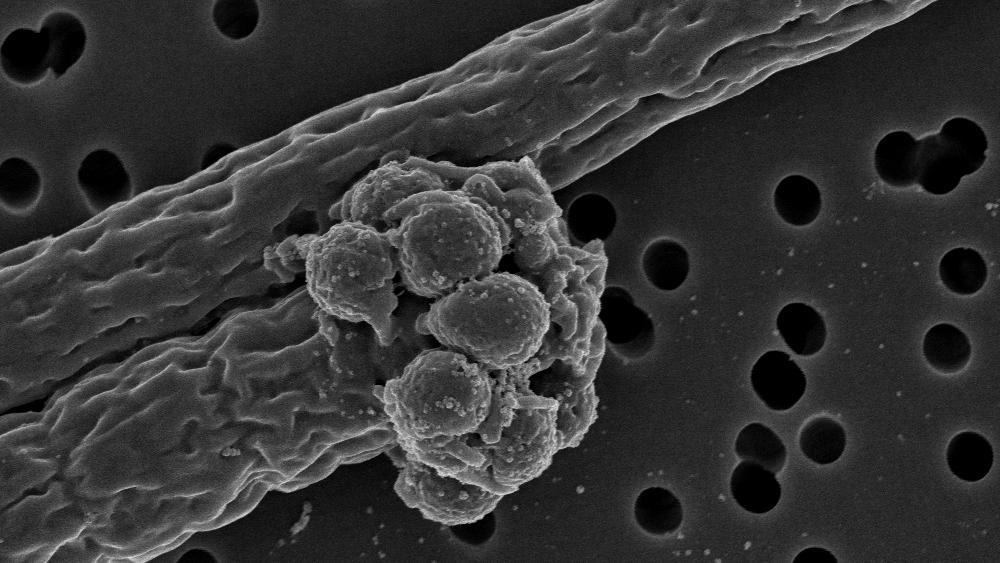

The micrograph, taken using a scanning electron microscope, shows two cyanobacterial filaments at 6000-fold magnification. The lower filament has been infected by several chytrid spores – the round structures at the tip of the filament. The parasite penetrates the filament, takes up the nutrients from its interior and uses it for its growth. This helps the spores to develop into bigger structures. Once the so-called sporangia are mature, they release new spores capable of infecting other hosts. | Image: Reingard Roßberg / IGB

Why is it that animal and plant species throughout the world have different genetic variants within their particular species, even though it is supposed to be the “fittest” gene pool that survives? According to a common theory in evolutionary biology, it is to enable the species to respond more effectively to changes in the environment, such as the occurrence of disease. However, experimental evidence to support this theory is very difficult to obtain: After all, it is virtually impossible to observe how evolutionary trends develop in most animal and plant species – their generation times are simply too long.

Evolutionary change in real time

A team led by IGB researcher and evolutionary ecologist Dr. Ramsy Agha has now investigated the evolution of the fungal parasite Rhizophydium megarrhizum. This parasite infects the cyanobacterium species Planktothrix, which is prevalent in many freshwaters. The team exposed the parasite to host populations whose individuals were genetically identical to each other, and alternatively to populations comprised of different genetic variants. Since the fungus multiplies rapidly, roughly once a day, the scientists monitored its performance for a total period of 200 days. “We wanted to observe evolutionary change in real time and under controlled conditions, to find out if and how quickly parasites adapt to genetically homogenous and diverse hosts,” explained Ramsy Agha.

The scientists permitted the adaptation of Rhizophydium megarrhizum, but kept the host populations in an evolutionary standstill. “We were able to show that the fungi adapt to genetically homogenous hosts very quickly, that is within just three months,” reported Agha. This adaptation is reflected in the fact that the parasites managed to adhere to the hosts and overcome their defence mechanisms more quickly, and were therefore able to reproduce more rapidly.

Genetic diversity in the host population slows down adaptation of parasites

If, on the other hand, the cyanobacteria were genetically diverse, these effects did not occur. The parasite failed to adapt, and the state of the disease remained unchanged. Genetic diversity in cyanobacteria evidently slows down the adaptation of the parasite, increasing their resistance to disease.

“Our findings are also significant for ecosystem research in general, because they help us to explain why a high degree of diversity in populations may be valuable for their preservation,” said Agha. He and his team want to investigate next what happens when not only the parasite, but also the host population is permitted to adapt to changed conditions. The researchers hope to gain further insights into how disease – generally perceived as a negative phenomenon – is a crucial natural process that promotes and preserves biological diversity.

Read the study in Frontiers in Microbiology >

Agha R, Gross A, Rohrlack T and Wolinska J (2018) Adaptation of a Chytrid Parasite to Its Cyanobacterial Host Is Hampered by Host Intraspecific Diversity. Front. Microbiol. 9:921. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00921