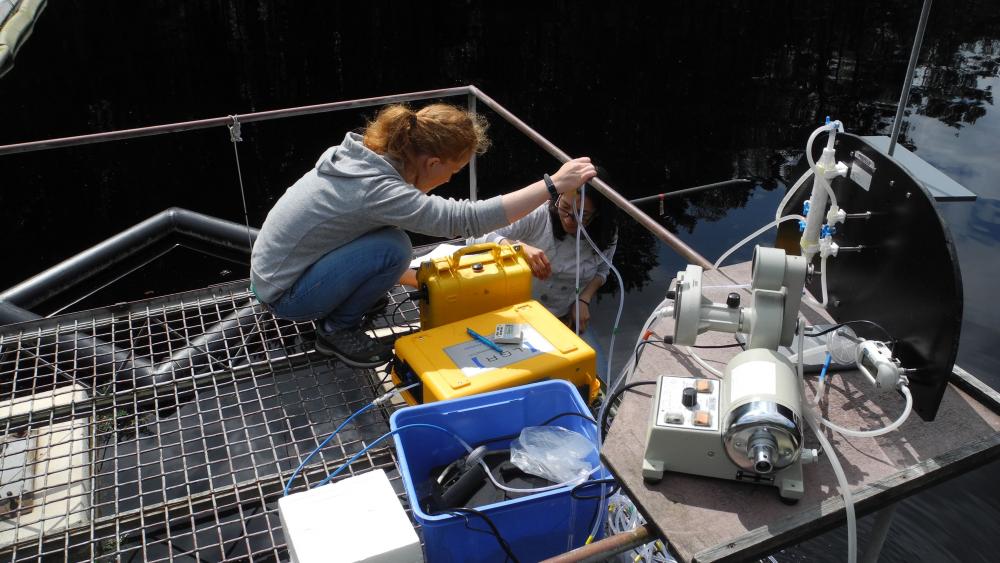

Nina Ulrich (left) and Karla Martinez-Cruz measure carbon dioxide and methane concentrations dissolved in the water of Lake Große Fuchskuhle using a MICOS apparatus.| Photo: IGB

Carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) are greenhouse gases, and they have an impact on the Earth’s climate. Both change the Earth’s radiative balance, and accelerate global warming. Natural emissions from lakes, rivers and wetlands also play a role. The Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) is involved in investigating the processes that lead to the release of greenhouse gases from water bodies.

Higher temperatures lead to rising methane emissions

Methane is normally formed in water bodies during the degradation of organic materials in sediments. It then rises from the bottom to the surface of the water in small gas bubbles and is consequently released into the atmosphere. This process depends on the temperature and the availability of organic material. For example, reservoirs in the tropics emit a particularly large amount of methane. Flooded rainforest areas and higher temperatures create an optimal mix for decomposition processes, and thus also for the formation of methane. For this reason, the global boom in dam-building could lead to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, which again would be facilitated by the rise in temperatures. A Dutch laboratory study involving the ITUC showed that an increase of only 1°C increases the release of methane from water bodies by 6 to 20 per cent. An increase of 4°C led to 51 per cent more methane emissions in the laboratory.

However, methane is not only formed in the sediment of lakes, but also in the oxygen-containing water column. In the warm half of the year, this process may even account for up to 90 per cent of methane emissions in some bodies of water. Researchers have discovered that blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) play an important role in this process. These organisms can form methane and also benefit substantially from climate change. In this way, global environmental changes such as global warming and the accumulation of nutrients in water (eutrophication) enable further methane formation.

At the same time, heat facilitates methane degradation

In principle, however, the methane formed in sediment or water can also be degraded in water directly, i.e. by microorganisms that metabolise methane. This is even possible under oxygen-poor conditions, because these microbes use other oxygen-containing compounds, such as nitrites, nitrates or sulphates. This anaerobic methane oxidation can remove one-third of the CH4 formed in the sediment from the emission. Like methane formation, this microbial process also depends on the temperature. Global warming can therefore accelerate both the formation and the consumption of methane.

Wetlands are natural methane sources

As a product of microbial degradation, methane is also produced in bogs. Globally, wetlands are the most dominant natural sources of methane. Especially large amounts of methane can be released from previously drained wetlands, which are restored by rewetting. Such rewetting has advantages for biodiversity and binds carbon in the peat of the growing moor. However, on the fens widespread in Central Europe, shallow lakes often form, which release large amounts of the greenhouse gas methane in the initial phase. In addition to the availability of organic material in the form of plant residues, a team of researchers has discovered another reason: If the peat soils continue to dam up, there will initially be significantly more methane-forming than methane-degrading microbes.

Role of urban waters is underestimated so far

Methane is also released when waters contain excessive concentrations of nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen, for example from urban lakes, canals or rivers. In many cities they occupy a considerable part of the surface area, in Berlin for example almost 7 percent.

As part of the DFG Research Training Group "Urban Water Interfaces", PhD students investigated the methane emissions from 32 Berlin water bodies. They found that small ponds with more than 150 milligrams of methane per square meter per day have the highest emissions, five times higher than the rivers. On average, the emission rates of water bodies in the urban area of Berlin were more than twice as high as global averages. Researchers suspect that the global trend towards urbanisation could lead to a further increase in greenhouse gas emissions from aquatic systems.

Higher CO2 emissions from dry water bodies

As the earth warms up, the number of rivers and streams that dry out completely or partially over the course of the year will also increase. “Intermittent waters,” as they are known, already account for more than half of the global river network. In the dry riverbeds of these bodies of water, considerable amounts of plant residues accumulate, from which – as soon as the water flows again – a surging release of substances takes place. This process leads to high CO2 emissions in the short term. An international team of researchers investigated 212 such rivers worldwide; they were able to prove that the release of carbon dioxide from these river networks was significantly higher than previously assumed in forecasts – by anywhere from 7 up to even 152 per cent.

Thawing permafrost soils release carbon and methane

In other parts of the world, for example in Siberia, global warming is leading to a decline in permanently frozen soil, known as permafrost. When this soil thaws, a huge amount of previously frozen carbon is released into streams and rivers. Scientists have found that such carbon is already being converted in the rivers of Western Siberia, and that these rivers therefore release more carbon into the atmosphere than they transport to the Arctic Ocean. On average, these rivers emit as much CO2 per square metre as a city the size of Leipzig per square metre. At the same time, considerable quantities of methane also escape from the thawing soils.

Recent findings have indicated that water bodies play an important role in the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Whether they act as sinks or as sources of greenhouse gases depends on specific environmental conditions. This fact demonstrates how difficult it is to estimate future emissions. If global warming increases and, at the same time, bodies of water become more polluted by high levels of nutrients, it can be assumed that emissions from water bodies will increase and thus accelerate climate change.